Culture

Chapter 7: The Ongoing Language Discussion in Ukraine

Natalie Poftak and Diana Shykula

The country of Ukraine has a deep-rooted culture of multilingualism. Like many other post-Soviet countries, Ukraine has struggled to define its national identity, and language discourse has been a prominent part of this struggle. The present state of Ukraine was part of multiple empires throughout history, including the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, the Austrian Empire, the Ottoman Empire, and the Russian Empire. Additionally, Ukraine’s unique location between Russia, the Black Sea, and Western Europe has made it a center of trade and cultural exchange in Europe, creating a multi-ethnic and multi-linguistic population.

Historically, Eastern Ukraine was ruled over by the imperial Russian Empire in the late 18th century, which had a specific cultural effect on the citizens of Ukraine. The practice of Ukrainian during Russia’s reign was not tolerated, thus enforcing the use of the Russian language. Due to this, Eastern Ukraine, including Sevastopol, Luhansk, and Donetsk, have a larger proportion of Russian speakers, in addition to the close proximity to Russia. The Western region has a history of being ruled by the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, which gave citizens free practice of speaking and practicing Ukrainian. This explains why the Western region of Ukraine, which includes Zakarpattia and Khmelnytskyi, has always had a higher proportion of Ukrainian speakers than Russian speakers. Surzhyk, a regional dialect considered to be a blend of Russian and Ukrainian, is spoken primarily in rural areas in Central and Eastern Ukraine. Because Russian and Ukrainian are widely used throughout the country, there has been debate about whether Ukraine should remain a bilingual or monolingual country. There are also several minority languages in Ukraine, such as Crimean Tatar and Yiddish; this chapter, however, will focus primarily on the language question in Ukraine centering on Ukrainian and Russian.

Language use, policies, and laws under Soviet rule

From 1923 to 1933, the leaders of the USSR chose to pursue a strategy referred to as “Ukrainization” to connect Ukrainians to the Soviet ruling party and differentiate Soviet leadership and policy from the previous Tsarist policies. The Russian Tsars used policies to limit Ukrainian language and the speaking of Ukrainian, and Soviet leadership chose to promote Ukrainian in the 1920s to gain support within Ukraine for their government. This process involved prioritizing the Ukrainian language in academia, teaching Soviet leadership in the country Ukrainian, and recruiting Ukrainians to the Party. Ukrainization contributed to the growth of education and literacy in Ukraine, and a nationwide literacy campaign brought the country to a 74% adult literacy rate in 1929 (Kubijovyč 1993). At the same time, 88% of Ukrainian students were in Ukrainian language schools (Kubijovyč 1993). Ukrainization contributed to the spread and support of the Ukrainian language. But under Stalin’s leadership, language policy drastically changed.

Stalin’s rule in the 1930s drastically shifted language policy from Ukrainization to Russification. Stalin did this to strengthen the Soviet Union, viewing multiple national cultures or languages across the USSR as detracting from Soviet Unity. Russification, in the context of the Soviet Union, referred to the state’s push for all member countries to speak Russian in day-to-day life, use Russian for government administration, and shed their cultural traditions and practices to focus solely on being Soviet member states. As the largest state in the USSR which was not ethnically Russian, Ukraine experienced an intense Russification effort from Soviet leadership, which had an incredible impact on Ukrainian literary tradition, and the Ukrainian language itself.

Part of Russification in Soviet Ukraine was the restructuring of the Ukrainian language itself. Soviet leaders worked to remove words from the Ukrainian dictionary and change the grammar structures, syntax, and spelling of Ukrainian. All of this was done to make Ukrainian more similar to Russian, with the ultimate goal of making Ukrainian almost like a regional dialect of Russian, instead of its own separate and distinct language. Russification in Ukraine also involved the imprisonment of Ukrainian intellectuals and cultural leaders, and the censorship of books, including sending lists to publishing houses of “banned Ukrainian words.” Another significant aspect of Russification policies in Ukraine was the change in state rules about translation. This policy forced Ukrainian translators to translate books from Russian, state published translations of books. This meant that all the new literature being distributed in Ukraine had already been edited and censored by state translators before they even reached Ukrainian translators, giving Soviet leadership control of these books and how they were interpreted.

.jpg)

Mykola Lukash

While Russification was being promoted in Ukraine, there were dedicated intellectuals working to preserve the Ukrainian language, who fought against the censorship of literature and risked lengthy sentences in labor camps to defend the use of Ukrainian. One of these people was the translator Mykola Lukash, whose story exemplifies both the extent of Russification in Ukraine and the lengths Ukrainian resistance members went to preserve Ukraine’s language and culture. Lukash began translating in the 1930s, when Stalin-era Russification was in full swing. He was frustrated by the state control over translation, which limited not only the books he could translate into Ukrainian, but also the way in which he translated. Lukash translated in secret, skipping the required “intermediary” texts, and was known for his flowery and rich use of the Ukrainian language in translations. Even as fellow translators and intellectuals were being imprisoned for their efforts to preserve the Ukrainian language, Lukash chose to create a Ukrainian language dictionary, commonly referred to as “Lukash’s Card Index.” This index took years to compile and included regional dialects, archaic dialects, and banned words. Unfortunately, this dictionary was never published due to Lukash’s being under heavy surveillance by the KGB. The card index is now kept in the National Academy of Sciences in Ukraine, and Lukash is remembered as a cultural hero and as the father of Ukrainian translation.

National Academy of Sciences in Ukraine, 2013

In addition to Lukash, there were many other intellectuals who worked to preserve the Ukrainian language. Two of them were Sviatoslav Karavanski and Ivan Svitlychnyi, who also worked to compile their own dictionaries, in their case while serving sentences in Soviet labor camps. Unfortunately, Karavanskyi was the only one of the three to be able to publish his dictionary, since he fled the USSR and finished it in the United States. The lasting impact of Russification on the Ukrainian language can still be seen today: without the work of people like Lukash, Karavanski, Svitlychnyi and others, many aspects of the language would have been lost forever.

The period of Stalin’s rule, which lasted from 1925 to 1954, was a brutal time for Ukrainians. A state-sponsored famine in the early 1930s killed millions of Ukrainians, and World War Two had further decimated the weakened nation. Languages like Yiddish or Romanian almost completely died out in Ukraine because of World War Two, and Russian continued to be promoted. The death of Joseph Stalin in 1954 led to the Crimean Peninsula being transferred to the UASSR and Ukraine finally being able to recover from World War Two. From 1954 to 1988, language policy in Ukraine remained much the same, with Russification still remaining the government’s official policy. In 1989, the Supreme Soviet of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic passed the “Law of Languages”, which declared Ukrainian as the only official state language, but guaranteed the protection of other languages spoken in Ukraine as well.

Language use, policies, and laws under Independent Ukraine (1991-2014)

On August 24th, 1991, Ukraine officially declared itself an independent state separate from the USSR. Following a referendum on December 1st of that year, in which 90% of Ukrainian citizens voted for independence, Ukraine formally left the USSR, which dissolved twenty five days after the referendum. Before the Constitution of Ukraine was formalized in 1996, the primary law guiding the country in matters of language was the 1989 Law of Languages. Article 10 of the Ukrainian Constitution, adopted in 1996, is similar to the 1989 law, declaring “The state language of Ukraine is the Ukrainian language” and reaffirming the protection of minority languages in Ukraine (Ukraine 1996).

At this point, Ukrainian was still the sole official language of governmental communication, both written and spoken, and the number of schools teaching primarily in Ukrainian was steadily increasing. A 2001 ruling by the Ukrainian Constitutional Court further affirmed Ukrainian as the primary language of communication in government. This 2001 ruling remained the dominant language policy from 2001 thru 2012, through three presidencies and two turbulent decades of Ukrainian history. The period of Leonid Kuchma’s presidency, which lasted from 1994 to 2005, was a time of corruption in government in Ukraine and closer ties with Russia. After the 2004 presidential election, the Orange Revolution occurred. The Orange Revolution was a protest against election fraud and government suppression of free elections led by supporters of the opposition candidate- Viktor Yushchenko. The Orange Revolution ended with the Supreme Court ruling in the favor of the protestors, asking for a new, truthful presidential election to happen. Yuschenko won and remained in office until the 2010 election. Under Yushcenko’s leadership, the Ukrainian language remained the dominant language of state government, and language policy did not change.

It wasn’t until Viktor Yanukovych, who was aligned with the Russian state, took office in 2010 that language policy drastically began to change. The phrase “language activist” appeared for the first time in the Ukrainian mass media in 2012, when protests against the language law developed and adopted by Victor Yanukovych‘s Party of Regions began. Called the Kivalov-Kolesnichenko law of 2012, this legislation granted the Russian language the status of a regional language, introducing a bilingual system in certain regions that allowed the use of Russian and minority languages in governmental institutions, including schools and courts. Although there were already many bilingual Ukrainians and citizens who preferred Russian or were ethnically Russian, this law nevertheless signified an important shift in Ukrainian language policy.

It is important to note that the social status of languages is not the same as the political status of languages, meaning that while a language such as Ukrainian may be used more in day-to-day life, it can still be viewed in a political sense differently from Russian, which had been the dominant language of the Soviet Union for more than seven decades. Due to direct action from the Soviet Union to discredit Ukrainian, Ukrainian was still viewed as a “lesser” language, and it took direct action on the part of the current Ukrainian government to promote the Ukrainian language and raise its political status. The importance of promoting the Ukrainian language in Ukraine was made only more evident by Vladimir Putin’s statements on the eve of Russian invasion of Crimea, when he stated that he viewed Russian speakers in Ukraine as part of the “Russian World” (Russkii Mir). Putin has continued to use this and similar language to support the false assertion that all Russian speakers, regardless of their political views and ethnic backgrounds, are considered part of the Russian World. Putin’s conflation of language use and national identity aims to discredit the sovereignty of the Ukrainian state, while at the same time advancing a Russian imperial agenda.

The Euromaidan from 2013-2014 consisted of hundreds of thousands of Ukrainian citizens getting together to protest Viktor Yanukovych’s decision to not sign an agreement with the European Union. Viktor Yanukovych prioritized economic ties between Russia and Ukraine, distressing many Ukrainians as it felt like betrayal for the hope of joining the European Union. The peaceful protest in Kyiv turned into the police using brutality against its own civilians, which is something that Ukrainians do not stand for, given the country’s long history of democratic traditions. The use of police brutality and the decision to strengthen economic ties between Ukraine and Russia enforced Yanukovych’s pro-Russian regime.

The Euromaidan, 2013

There was a noticeable link between language use and political preference during the Euromaidan between Russian and Ukrainian. Those who posted in Ukrainian on Facebook were more likely to express positive views about Euromaidan compared to those who posted in the Russian language (Slobozhan et. al, 107). This emphasizes that language signals political preference, stressing how Ukraine is a divided society. The wave of language activism strengthened after Euromaidan and continued to grow after the annexation of Crimea and rise of Russian aggression in Donbas. Ukrainian language is now held in higher regard after the post-Euromaidan protest both as a national language and a symbol. There was a moderate decline in the already fairly low support for Russian as a state language, which by 2015 was supported by less than a quarter of the population. Both the decline of Russian as a state language and the widespread identification with Ukraine as a free and independent country suggest a growing consensus about the use of the Ukrainian language to reflect the legitimacy of the Ukrainian state.

Constitutional Policies

The Constitution of 1996 was Ukraine’s first constitution as an independent state. From just previously disbanding from the Soviet Union, many of the articles adhere to the usage of Ukrainian language because of the large Russian speaking population in Ukraine. In 1996, the Constitution declared Ukrainian as the single official state language for the entire country. Article 10 states that the use of Ukrainian language should be used in “all spheres of life”, of social life, while also guaranteeing development and use and protection of Russian and other minority languages (Besters-Dilger, 258). So whilst this policy definitely promotes the use of Ukrainian and the spread of the language, it does not dismiss Russian as a language used by the citizens. However, the language of the official print media, television, and radio is in Ukrainian. Private broadcasters must also air at least 60% of their programs in Ukrainian. The state’s constitution has gone through an extra effort to maintain a large Ukrainian speaking population with these policies. However, minorities (Russian-speakers and other languages) still have the right to publish newspapers, journals, and books, and to broadcast in other languages besides Ukrainian (Article 21). Whilst the Constitution and the State clearly supports a majority speaking Ukrainian population, it does not dismiss the right of people to subjectively choose between speaking Russian and Ukrainian, as minority languages are given rights as well.

Language use, policies, and laws under Russian attack/invasion (2014 to the present)

Contrary to popular belief in many countries around the world, the war between Russia and Ukraine did not begin when Russia launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022. In fact, the declared Russo-Ukrainian War had begun eight years earlier on February 20, 2014, when Russia annexed Crimea and promoted a separatist movement and military conflict in the Donbas region of Eastern Ukraine. In 2016, Putin justified these actions by claiming that Russia “had to protect the Russian speaking population in Donbas.” Six years later, he repeated the same rhetoric of protecting Russian language speakers in Ukraine to justify the so-called “special operation” launched in February 2022 (Lanvers et al. 28). During the initial breakout of the war in 2014, language activism and policies began to further enforce the use of the Ukrainian language instead of the Russian language. This was done to strengthen the Ukrainian population and to urge the language conversation from Russian to Ukrainian.

Since 2014, many efforts have been made to increase the use of the Ukrainian language in order to make it not secondary to the Russian language. One example is language activists on social media platforms urging citizens to switch from Russian to Ukrainian from 2012-2016 due to the conflict between Ukraine and Russia (Kiss 106). Organized protests broke out to improve the use of the Ukrainian language, thus increasing Ukrainian and directly impacting political decisions. The wave of language activism was strengthened after Euromaidan and followed by the annexation of Crimea and the rise of Russian aggression in Donbas (Kiss, 108). Many Ukrainians increased their efforts to learn Ukrainian, especially Russian-dominant speakers in the East. To further understand the importance of speaking Ukrainian, the website of the Constitutional Court of Ukraine makes it explicit: “The threat to the Ukrainian language equals the threat to the national security of Ukraine” (Appendix 2:2).

In April 2017, the Kyiv City Council adopted a draft law stating that the Ukrainian language should be the first language of addressing clients in city establishments, where Russian is a predominant language. This is one example of a language policy that combats the majority use of Russian. In efforts to limit the dissemination of Russian texts in the country, the Ukrainian government banned the import of commercial books from Russia in 2017. From these policies it is clear that the state supports the Ukrainian language as part of a broader political agenda to assert Ukrainian independence and sovereignty.

To directly grasp the Pro-Ukrainian stance, stated is a direct quote from a Ukrainian citizen: “Ukrainian identity and culture are impossible without the Ukrainian language, so our task in the period of the Russian intervention and general processes of globalization is to save and develop our language” (Kiss, 121). Many Ukrainians continue to feel this way now, especially after Russia’s full-scale invasion. It is important to note that some Ukrainians feel that the continued use of Russian in Ukraine threatens to extinguish the Ukrainian language and culture, and that for this reason it is crucial to continue to use Ukrainian state-wide. They maintain that Ukrainian promotes national identity, patriotism, and pro-Western foreign policy, and that Russian reflects the ideology of the Russian World, authoritarian attitudes, and pro-Russian imperial ideals dating back to the USSR and even tsarist times (Kudriavtseva, 154). This way of thinking, in addition to the full scale invasion, has posed Russian as the “enemy language.” According to Kulyk’s study, Russian is now considered to be the language of the enemy and thus, many Ukrainians refuse to utilize Russian and instead try to use Ukrainian, as it is now considered to be the language of the resistance (Yao et. al, 9).

Language Policies in Education

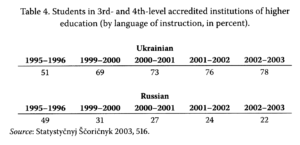

In September 2017, the Ukrainian Parliament implemented a new naw on education, according to which the only language to be used in public education should be Ukrainian. Minority languages and the regional language of Russian are allowed to be used in the instruction of private schools. The law declaring Ukrainian as the sole language of public education has constituted a major step towards educating youth to fully master the Ukrainian language. However, it is evident that many Ukrainians still code switch between Russian and Ukrainian based on social preferences. For instance, although Ukrainian is taught and spoken in schools, many people still speak Russian with their family and friends at home and in different social environments. This point underscores the ongoing debate in Ukrainian society concerning one’s “mother tongue” (or language spoken in the home) and “native language” (or language spoken in the broader society) Students educated in Russian-speaking private schools do, in fact, more often choose Russian as their native language than the students from the Ukrainian-speaking schools (Kudriavtseva, 157). Russian speaking schools still exist because all public institutions run by the state are instructed in Ukrainian, not counting private schools. Due to historical ties with Russia and regional differences, the largest numbers of Russian-language secondary schools are located in Eastern and Southern Ukraine in cities such as Kharkiv, Odesa, Dnipropetrovsk, Zaporizhzhia, Donetsk, Luhansk, and Kherson (Kudriavtseva, 155). In the Crimea and in eastern Donbas region, now occupied by Russia, all higher educational institutions use Russian as a language of instruction. Levels of Russian language are significantly higher in regions where instruction is conducted in Russian. Another reason there are Russian speaking schools is due to Articles 11, 24 and 53 of the Ukrainian Constitution, which define the rights of minorities as ensuring the right to be taught in one’s mother tongue at school and in cultural societies, or to use the mother tongue as a teaching language and municipal educational establishment. The following tables illustrate the decline in use of Russian and the increase of instruction in Ukrainian in schools between 1995-2003, as well as regional differences at different levels of education.

Table showing language of instruction from 1995-2003

Table showing regional differences of institutions in the use of Ukrainian

As both data indicate, Ukrainian is the predominant language of instruction in most areas of the country, indicating that the majority of the country knows Ukrainian. Still, there are great variations in which language a person chooses to speak in a given social context.

Analysis of language patterns now all over Ukraine (East, West, Central, South)

The ongoing debate between the use of Ukrainian and Russian still varies considerably by region. Historically, Russian has been spoken predominantly in the East, while Ukrainian has dominated in the West. As the data below illustrate, this divide was still very much in evidence in 2021.

Figure showing use of Ukrainian language percentage

Regions like Crimea, Sevastopol, Luhansk and Donetsk that are geographically closer to the Russian Federation employ Russian more than Ukrainian even before Russia’s occupation of these regions. However, increasingly there are efforts to introduce Ukrainian to the Eastern population, with Ukrainian courses now available for anyone wanting to learn the language (Kiss, 116). Many Russian-speaking Ukrainians are switching from Russian to Ukrainian, especially residents in the east where themajority is Russian speaking. There are regions in Ukraine that have demonstrated rapid growth of Ukrainian language usage, such as Zakarpattia and Khmelnytskyi in the south-west regions of the country. As for regions such as Crimea, where less than 10% of Ukrainian is spoken (as of 2019), the effect of Russification is stronger than the corresponding Ukrainization effects in other Ukrainian regions. However, it is predicted that at this growth rate, the use of Ukrainian is increasing country-wide and will be in great demand in the future.

Conclusion

The language debate in Ukraine has been a central issue in Ukrainian society for centuries, and its importance has only deepened due to the effects of the Russo-Ukrainian war. The country has enjoyed a history of multilingualism, and an open question today is whether Ukraine should remain a multilingual, primarily bilingual, or a monolingual state. Russian is now experienced by many as being the language of the oppressor; however due to the close proximity of Eastern Ukraine to Russia, it is highly unlikely that the Russian language will ever disappear from Ukraine altogether. That said, given the efforts to promote Ukrainian identity among the citizenry through new language and educational policies, it is clear that the entire population of the country will likely know Ukrainian in the future. It is solely up to the citizens of Ukraine to choose whether to continue speaking Russian or not, but the implementation of Ukrainian language state-wide has helped the country unify and understand the importance of the Ukrainian language. Ukraine is a western country based on cultural pluralism and the agency and personal choice of individual citizens. Due to this war and language policies, Ukrainians are fighting for wide-spread growth and use of Ukrainian, while also simultaneously fighting for the right to choose which language to freely speak.