Culture

Chapter 8: Women, Gender, and Activism in Contemporary Ukraine

Eliza Brennan and Hannah Prescott

- Women in Ukraine after 1991

The fraught history of feminism in Ukraine

Since before the start of Ukrainian independence in the 1990s, women have fought to gain rights and develop a place in Ukrainian society. Ukrainian culture and identity cannot be complete without the inclusion of women’s experiences and differing perspectives based on gender and sex. Unfortunately, the fight for Ukrainian women’s safety, freedom, and rights has been fraught with violence and backlash from society and the government. They have experienced brutal crimes and societal expectations based on their sex and have responded with protest, culture, and defiance. Oftentimes women will become the victims of war and poverty as the chaos takes down protections from human trafficking and sexual assault. Because Ukraine is in an active war right now, it is imperative that we understand how women fit into the complex culture and history of the country and how war has disrupted their position in Ukraine. Women are not required to fight for Ukraine, but with expanding rights and freedom, many choose to do so. They also play essential roles as citizens of Ukraine and in contributing to culture and art. Many Ukrainian women have advocated for themselves and femininity to obtain and maintain equality and rights. They do so with protests, demonstrations, and different types of art. Women play an essential part in Ukrainian culture that can often be overlooked but is rich with perseverance and development in rights breakthroughs in an ongoing struggle for equality during wartime and unrest.

Women and economic collapse in the 1990s

Women’s position in Ukraine was perilous during the 1990s. The fall of the Soviet Union and a failure in market reforms caused Ukraine to fall into an economic crisis. The aftermath of this economic collapse had a disproportionate effect on the female population of Ukraine. The Soviet Union originally had a government-run economy and when this collapsed, the economy was privatized and illegal organizations that were part of the shadow economy before became frontrunners. This promoted organized crime and made it easier for human trafficking. “Organized criminal networks” became widespread and available and human trafficking increased due to extreme poverty and many young women were sold into sexual slavery (Denisova). During the 1990s, over 100,000 women were victims of human trafficking in Ukraine. Many of these women were unaware of where they were headed, believing to be on their way to becoming employees of a hotel, such as waitresses or maids (Malynovska). Another phenomenon that was a reaction to this economic crisis and negatively affected women was “mail-order brides.” For “four thousand dollars” or around that price point, Ukrainian women were chosen off of a website based on their photos and taken, or trafficked, to the United States, or other Western countries to marry their buyers. For example, the website “KievConnections.com” contains “three images, body, and self-descriptions, location, [and] language proficiency” (Barton). This system took advantage of desperate Ukrainian women who were victims of poverty.

Key Legislation in the 1990s and 2000s

The 2000s marked an important period for women and gender equality. Throughout the 2000s the Ukrainian government took many steps to eradicate gender differences and released many documents that promoted gender equality. In efforts to reduce violence against women Ukraine subscribed to ‘16 Days of Activism against Gender Violence’ which runs from 25 November to 10 December every year. Additionally, around the same time, Ukraine signed the U.N. Millennium Declaration and released a nationwide public information campaign on gender awareness. The U.N. Millennium Declaration consisted of 8 developmental goals to be completed by 2015 with goal 3 promoting gender equality and the empowerment of women (Marian J. Rubchak 60). Later, on November 15, 2001, the Law of Ukraine on the Prevention of Violence in the Family was passed. This piece of legislation was preceded by other acts including a presidential decree that was intended to upgrade the social status of women. Lastly, in 2005 three national action plans regarding gender were put into place. These action plans addressed career discrimination, human trafficking, media, education, etc. At this point, independent Ukraine was shifting towards a more European view on gender equality, but naturally, this would all change when Victor Yanukovych was elected. Victor Yanukovych ran a pro-Russian platform and made his views on gender clear when he would not participate in pre-election debates with Yuliya Tymoshenko. (Hankivsky, Salnykova 12)

Women’s Participation in the Revolution of Dignity

The Revolution of Dignity, also known as the Euromaidan, occurred from November 2013 to February 2014. As explained in Chapter 3, the Euromaidan was the result of President Viktor Yanukovych’s sudden decision to not sign a political association and free trade agreement with the European Union, and instead create closer ties with Russia. The goal of the Revolution of Dignity was to present Ukraine as European – not Russian – so Ukrainians could be free from their history of Soviet Union and Russian Federation dominance (Channel – Justice 717). About 400,000 – 800,000 people participated in the protests with almost half of the participants being women. Protestors and state forces clashed in the capital of Kyiv resulting in the death of 108 civilian protesters and 13 state police officers. According to interviews, women had a wide range of motivations for participating in the public protests, including dissatisfaction with the government; solidarity with other protestors; motherhood; civic duty; and professional service. Feminists and leftists believed that Europe would provide a more progressive lifestyle because Europe promised to decrease the gender-based pay gap and encourage equality among men and women (Channel – Justice 719). Women’s roles in the Revolution of Dignity varied; professionally some women were put in charge of coordinating medical supplies and organizing a missing persons list, while they marched down Kyiv square with signs.

Backlash and physical attacks against women during the Revolution of Dignity

During the first weeks of protests, many feminist and leftist actions took place which indefinitely resulted in violence. Feminists and leftists carried signs with slogans such as; “If you’re afraid of gender you can’t be a part of Europe” and “Do you want to be a part of Europe? Say no to sexism and homophobia.” After only a few minutes of standing in Kyiv square a protester holding a sign that read; “Europe is tolerance” had it ripped from her hands which sparked a violent uprising. Protestors surrounded the leftist group and forcefully pushed them down a small stairway at the center of Kyiv Square and within a few minutes all of their signs had been destroyed (Channel – Justice 721). Another instance of violence occurred on November 28th when a women’s rights street action peacefully protesting with slogans such as; “European salaries for Ukrainian Women” and “Europe means paid maternity leave,” were attacked by 30 masked men from the conservative party armed with tear gas (Zychowicz 94). These attackers were physical, and brutal, and referred to themselves as the security of the Euromaidan.

II. Prominent Ukrainian Women Activists: FEMEN and Feminist Ofenzywa

Activists fight for gender equality not allied with the state

Two of the most famous women’s activist groups within Ukraine are FEMEN and the Feminist Ofenzyva. These initiatives, although very different from each other, have worked toward the goal of advancing gender equality. These initiatives also did not interact with the state as they refused to create a relationship with it or participate in the following actions: writing or signing petitions, teaching government authorities how to avoid sexism, collaborating with state institutions, or advocating for legislative reforms.

FEMEN

FEMEN is a very radical Ukrainian feminist protest group formed in 2008 after extreme frustration with behavior towards women in Ukraine such as human trafficking, domestic violence, and unequal treatment. They utilized provocative forms of protest including protesting topless with their messages written across their breasts. Individuals who participated in the FEMEN activist group believed that they were stripped of the right to their bodies; they used the naked body to express hatred towards the patriarchal order. Although these seem like drastic measures, their actions brought attention from across the world and gave them a large amount of news coverage that helped to promote their purpose and gain followers. FEMEN’s most active years were from 2008-2012 in which they staged about fifty-five different protests for various feminist issues (Zychowicz 33). Because FEMEN was so extreme they were denied as an activist group because they often exploited the female body in their protests, and they received fierce criticism from women’s NGOs and gender/feminist communities because of their protest style. In 2013 FEMEN was forced to flee Ukraine because of the brutal police searches conducted at their office and the repeated physical attacks on FEMEN activists (Zychowicz 91).

Feminist Ofenzyva

The Feminist Ofenzyva was founded in 2010 as a radical separatist feminist activist group. The group was active for three years before deciding to close by group consensus on January 17th, 2014. The goal of Feminist Ofenzyva was to support females’ voices in the public sphere. They fought to overcome patriarchal forms of power in Ukraine and its manifestations such as sexism and homophobia. The Ofenzyva had 6 major goals, 1: create space for gender studies, activism, and support for women, 2: Introduce sexual education in schools, 3: Achieve economic rights for women such as equal pay, 4: reproductive rights for women, 5: Achieve equal legal protection for all types of relationships, and lastly 6: domestic and sexual violence laws to protect women. They attempted to make a difference by participating in street activism and demonstrations, organizing conferences, and writing articles. Oftentimes, the Feminist Ofenzyva was pushed out of the media by non-profit organizations that were also pursuing gender equality.

III. Women and War

Russia’s Invasion of 2014 and its Impact on Women

The Russian invasion of Ukraine began in 2022, but there has been conflict between the two countries for over eight years, beginning in 2014 (Walker). This conflict, as always, has perpetuated violence and mistreatment of women as the country is distracted with defending against Russia and has also exacerbated violence towards women from Russia. Since the beginning of the Russian-Ukrainian conflict in 2014, when Russia annexed the Crimean Peninsula and led separatist movements in Eastern Ukraine, women have been forced to step into different roles economically and socially. Men between the ages of 18 and 60 have been required to report for military service, which means leaving their families and wives behind. Traditionally, men in Ukraine have been the head of household and the breadwinner for their families, but in times of war, when they are fighting, women must take on these new roles. In addition to a change in family structure, women are also forced to migrate or rebuild their communities because of economic collapse, displacement, or food shortage. The war and disappearance of men have separated and torn apart families, leaving many women as the sole providers and caretakers of their children and homes.

Impacts of the full-scale invasion on women and children (effects of the draft and mass migration)

Because of the separation of families in which men are forced to fight and women become the sole caretakers of their children, families, and homes, many women and children are migrating as refugees separated from their husbands and the men in their families. About eight million refugees from Ukraine, mostly made up of women and children have been displaced and recorded to be in Europe (Cimino). With conflict comes a breakdown of institutions and law which increases the likelihood of human trafficking among the constant movement and escape of refugees, especially in women. There is a high risk of human trafficking in migrating out of Ukraine at the moment and women are the main targets of this (Cimino). Girls and young women are the most likely to be displaced during conflict of this scale and the responsibility to get the family out of harm’s way usually falls to the woman or mother figure, so movement and migration as an escape is common. Many Ukrainian women have taken on this responsibility and migration becomes their only option and this decision falls to them to make as there is no longer men in their household.

Sexual violence against women

During conflict, women are also disproportionately affected by “gender-based violence” or sexual violence. Sexual violence is extremely prevalent in the Russo-Ukrainain conflict as Russia has been accused of using rape as a tactical war strategy. Like chemical weapons and landmines, rape has been banned by international conventions. Women have increasingly become the victims of war, and rape has become the most frequent weapon used against women (Cimino). For example, women have testified that Russian soldiers are equipped with an erectile dysfunction medication known as Viagra used to more efficiently rape civilians (Al Oraimi, Suaad; Antwi-Boateng, Osman 9). Women are also more likely to be exploited sexually when in an economic crisis which has been exacerbated by the ongoing war. This economic crisis can increase human trafficking, and desperation among women, and displacement and sex can become a currency to trade for resources such as food (Al Oraimi, Suaad; Antwi-Boateng, Osman 9).

Women’s participation in the war effort

Women are participating in the ongoing war efforts against Russia in many different ways. Ukrainian women serve in the military, raise their children during wartime, and provide other essential services. For example, women have served as anti-war activists, diplomats, front-line soldiers, and heads of households. Many are “holding down the fort” and keeping their homes and institutions in place, but oftentimes they are displaced and forced to rebuild communities. Although women were not required to report for combat duties like men aged 18-60, a poll conducted in March 2022 demonstrated that 59% of Ukrainian women were willing to fight (Al Oraimi, Suaad; Antwi-Boateng, Osman 6). Additionally, there are 60,000 women in the Ukrainian military and about 5,000 of them are part of combat units as paramedics or snipers (“Ukrainian”). Many women who see combat are assigned the role of a sniper, and women participating in the fighting and joining the Ukrainian armed forces have only increased since the beginning of the Russian invasion (Malchevska). If they are not actively fighting, many women are taking over previously men’s roles in their community. With men away fighting, women are running institutions such as hospitals or schools, often without resources, electricity, or running water (“Ukrainian”). Women’s participation in the war efforts are not to be looked over and they have contributed to Ukraine’s resilience and defiance during difficult times.

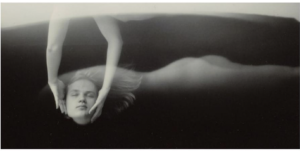

Women’s artistic responses to the war: poetry and photography

Throughout Ukrainian history, art has been used to critique, protest, and send a message to the public about the government, and state of the country, and create conversation about specific issues. Ukrainian women have responded to the conflict with Russia today in poetry and photography. Recent publications from Ukraine include Words for War: New Poems from Ukraine put together by the husband-wife duo Oksana Maksymchuk and Max Rosochinsky. This partnership emulates a modern take on Ukrainian marriage and promotes the development of women’s participation in protest and writing. Within the pages, women poets such as Lyuba Yakimchuk and Marianna Kiyanovska write about how war and fighting have changed their perception of themselves and how they’re seen as human beings. This change gives the reader an idea of how the fighting in Ukraine has altered citizens, and women’s identity and their poetry is an attempt to reconcile with this and turn to the general public, in Ukraine and beyond, to advocate for the cease in fighting and conflict in their countries (Maksymchuk). Female Ukrainian poets who comment on conflict in their country and its effects on women include Marianna Kiyanovska, Halyna Kruk, Oksana Lutsyshyna, Marjana Savka, and Lyuba Yakimchuk. Their voices and art have exposed the women’s experience of war in Ukraine and how it has negatively impacted them. Their words bring emotions and motivation to end the fighting and find sympathy in new places. Modern female photographers from Ukraine include Alena Grom, Olena Morozova, Maryna Brodovska, Julia Po, Yulia Krivich, Olia Koval, Polina Polikarpova, Olena Bulygina, and many more (“Reclaiming”). These artists range from creative photographers who want to send a message and express themselves through this medium to photojournalists interested in documenting life in Ukraine, and, especially now, life in Ukraine during wartime. Many of these photographers’ works resemble the female experience in Ukraine and beyond Ukraine as well. Their efforts to include everyday life experiences and also take a critical look at the conflict in Ukraine and its effect on female life through photography are manifested among their photos. Many of their photographs document women’s lives in Ukraine during the war with Russia and their feelings towards it.

Alena Grom

Victoria (from the Between Borders series)

Uzhhorod, Spring 2022

Olia Koval

Everything will Flow (from the Non-violent Changes series)

Olena Morozova

I don’t hear them (from the Granny series, 2019-2022)

Alena Grom

Girl With a Doll (from the Warehouse of Toys series)

Donbas region, 2017