Main Body

Intersectional Feminism

Nina Bakum, Fernando Rufino

INTRODUCTION

Intersectionality as a concept has a deep and complex history within feminism and feminist theory. Intersectionality refers to the interconnected nature of certain social categories such as gender, race, and class. Intersectionality occurs when these social categories overlap, and create interdependent systems of discrimination (Oxford English Dictionary). The term was officially coined by civil rights advocate, writer, and scholar, Kimberlé Crenshaw in 1989. Crenshaw, looking for a way to categorize women of color’s exclusion/discrimination based on both gender and race, officially defined the term in her article, Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics. Intersectional feminism aims to advocate and fight for those who experience oppression within these overlapping social categories. Although the term was not officially defined until 1989, the concepts of intersectionality were advocated by early black feminists to try and address their systemic disadvantage as both women and people of color.

Kimberlé Crenshaw

Source: Columbia Law School

GENEALOGY

The term intersectionality stems from as early as the 1890s from Ana Julia Cooper a black feminist and liberation activist. Cooper described the unique position black women held in the country based on their intersection of being black and a woman. In these early years, black women were not acknowledged for both identities in the country’s patriarchal judicial systems. Since there was no term for intersectionality, black women who often experienced discrimination and oppression for both their race and gender were called “double- handicapped” a term used by Mary Church Terrell (Cooper 2016, 387).

This term came after black women recognized that white women only had to face gender discrimination, while black women had to confront both gender and racial discrimination. This intersection of identities intensified the discrimination and oppression that black feminists often experienced. Today, it is important to note that these definitions may have been limited at the time, as we now recognize that white women may also have other distinct identities such as ability, class, and citizenship which intersect with their daily lives.

The roots of intersectionality stem from the writings of black feminists who progressively produced literature that discussed the complex relationship of the identities they held. These writings explored the discrimination and oppression these women experienced. As black feminism grew momentum the concept of intersectionality took shape. The literature addressing intersectionality progressed into the late 1980s when Deborah King attempted to account for other identities like class. By doing this she used the term “multiple jeopardy” which built upon previous black feminists who coined the term “double jeopardy” (Cooper 2016, 388).

INITIAL USAGE AND EXPERIENCES

The initial waves of feminism primarily emerged from the experiences of white women who often failed to address the distinct challenges faced by black women. This exclusion may have been rooted in implicit racial bias which limited the perspectives of black women in the early waves of feminism.

Women’s rights activist and abolitionist Sojourner Truth describes the distinct experiences between white and black women in her 1851 speech Ain’t I A Women where she states, “Nobody ever helps me into carriages, or over mud-puddles, or gives me any best place! And ain’t I a woman?” (Truth, 1851).

Similarly, the experiences of black women were often overlooked within the black community and primarily focused on the experiences of black men. This marginalized black women even further as it hindered their ability to engage in feminist practices and liberatory movements. The Combahee River Collective, a black, queer, and feminist organization was developed in response to this alienation. In 1977 the collective released a statement discussing the issues black women experienced in white feminism stating, “….we are actively committed to struggling against racial, sexual, heterosexual, and class oppression, and see our particular tasks the development of integrated analysis and practice based upon the fact that the major systems of oppression are interlocking” (Combahee River Collective, 1977). Their statement also addressed how the Black liberation movement was dominated by cis-gender men. They called this idea, interlocking oppressions.

JUDICIAL SYSTEM CONFLICT

In lieu of these women’s experiences, Kimberlé Crenshaw began her research in an attempt to define the struggles these women were facing. In her article, Crenshaw describes three Court Cases that illustrate the meaning and importance of intersectionality, DeGraffenreid v General Motors, Moore v Hughes Helicopter, and Payne v Travenol. In DeGraffenreid v General Motors, five black women sued General Motors for not hiring black women, and subsequently laying off black women that they did hire (Crenshaw 1989). The court concluded that because General Motors hired women (albeit white women), these women could not sue under the guise of sex discrimination, and suggested that they consolidate their case with another case that had to do with racial discrimination, refusing to see the women’s claims as both sex and racial discrimination.

In Moore v Hughes Helicopter the plaintiff provided evidence of race and sex discrimination in promotions to upper-level craft positions and to supervisory jobs. As Crenshaw argues, the court dismissed Moore by rejecting her bid to represent all females because her “attempt to specify her race was seen as being at odds with the standard allegation that the employer simply discriminated ‘against females’” (Crenshaw 1989, 144).

Finally, in Payne v Travenol, two black women filed a class action lawsuit on behalf of all black employees at a pharmaceutical plant. The Court found that there had been racial discrimination at the plant, but refused to extend the “remedy” to black men (Crenshaw 1989, 149). Crenshaw uses these court cases to explain that black women face discrimination from a number of different avenues, and therefore their experiences can not be looked at simply through the lens of one social categorization.

MODERN USAGE AND EXPERIENCES

With these cases in mind, Crenshaw looks to conceptualize and define intersectionality, In her article Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics, Crenshaw writes, “With Black Women as the starting point, it becomes more apparent how dominant conceptions of discrimination condition us to think about subordination as disadvantage occurring along a single categorical axis. I want to suggest further that this single-axis framework erases Black women in the conceptualization, identification and remediation of race and sex discrimination by limiting inquiry to the experiences of otherwise-privile” (Crenshaw 1989, 140). Crenshaw uses the analogy of a traffic intersection to define the term intersectionality. At an intersection, there are cars (aka different marginalized identities) traveling from all different directions. When an accident occurs at an intersection, it is caused by any number of cars traveling from any number of different directions. Intersectionality is the act of taking into account these different marginalized identities when thinking about discrimination and systems of oppression. Feminism that takes into account female identifying people who are part of multiple marginalized identities, is considered intersectional feminism.

Source: https://thekidshouldseethis.com/post/what-is-intersectionality

CONCLUSION

In today’s society, people often have to navigate multiple intersecting identities that shape their daily experiences. For instance, there are disabled Latina women, queer disabled folks, trans undocumented immigrants, low-come BIPOC folks, and other people who have multiple intersecting identities.

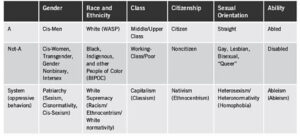

As Feminist theory, critical race theory, and sociology grow, scholars like Cherise A. Harris and Stephanie M. McLure continue advancing these studies with new research and theory. In their book, Getting Real About Inequality, Harris and McLure introduce the acronym and chart known as GRECCSOA, which stands for Gender, Race, Ethnicity, Class, Citizenship, Sexual Orientation, and Ability. This chart aims to list some of the major identities that are involved in intersectional analysis while also acknowledging the levels of privilege people may hold. The chart below provides a more complex way of approaching intersectionality instead of oversimplifying people’s identities (Harris, 2022).

Harris and McLure also acknowledge that their research comes with limitations by not including identities such as Religion or Age. This acknowledgment allows other scholars to continue advancing and adding to this literature. As intersectionality grows we start understanding the complex nature of everyone’s identity.

REFERENCES

Crenshaw, Kimberle. “Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory, and Antiracist Politics [1989].” Feminist Legal Theory, 2018, 57–80. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429500480-5.

Disch, Lisa, Mary Hawkesworth, and Brittany Cooper. “Intersectionality.” Essay. In The Oxford Handbook of Feminist Theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016.

Harris, Cherise A., and Stephanie M. McClure. Getting real about inequality: Intersectionality in real life (IRL). Los Angeles: Sage Publications, 2022.

Oxford English Dictionary, s.v. “intersectionality, n., sense 2”, July 2023. <https://doi.org/10.1093/OED/8904687553>

“The Roots of Intersectionality.” University of Rochester School of Nursing. Accessed October 9, 2023. https://son.rochester.edu/newsroom/2022/intersectionality.html.